Saturday, September 29, 2012

Migrations

It is autumn once again, and as I prepare to leave Maine tomorrow at the end of another restful summer season here on the shores of Sabbathday Lake, I watch our many feathered friends who are in the midst of their own migrations to gentler winter climes. Here is wishing everyone a very pleasant autumn season wherever your travels or other adventures might take you.

Monday, September 24, 2012

Trending Toward Monhegan - Dispatches from Maine

| |

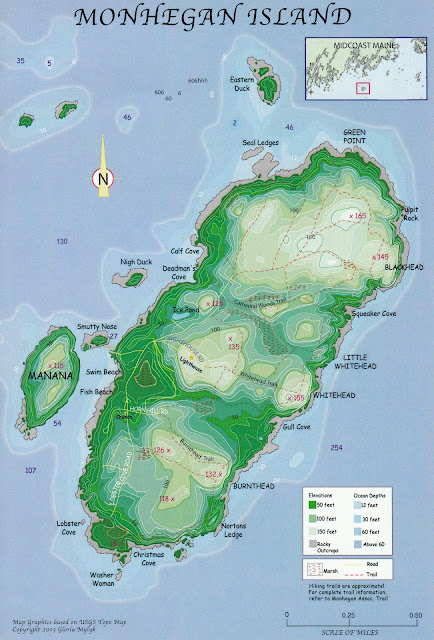

| Copyright 2003 by Gloria Mylyk. Used with permission. Do not reproduce without permission. |

I have been telling people for the past few years that one of these days I am going to write about Monhegan Island. After visiting the island three times this summer, I am finally making good on that promise. My thanks and appreciation go out to Ruth Grant Feller, Holden Nelson, Joan Rappaport, Stan and Marion Gurspan, and many others for their stories and willingness to share them with me.

__________

Every summer since 2001 my wife and I have been spending time on Monhegan Island. This year we could not have picked a more delightful time to go. After a cold and very wet spring followed by a stormy early summer with its murderous heat, the island was on the threshold of glorious weather when we arrived in early August. It was equally beautiful later in August when we made a day trip to the island with our son Ian, who had not been there in five years, and his wife Katie who had never been to Maine. Finally, our friend Becky Parsons, who was visiting from Virginia, joined us for another day trip this past week. The summer season was over and there were fewer visitors milling about. The local lobstermen were preparing their traps for the beginning of their season on October 1.

In Orhan Pamuk’s short essay “The View,” one of his frequent contributions to the Turkish political humor magazine Oküz [Ox], he describes a horse carriage ride he and his young daughter shared around Haybeliada, one of the Princess Islands in the Sea of Maramara, near his native Istanbul. Pamuk has spent many of his summers since childhood on this island and he wanted to share it with his daughter and to see it fresh through her eyes. At one point the carriage pauses at the head of a precipitous cliff where they were able to enjoy the broad panorama. “Beneath us there were the rocks, the sea, and rising out of the steam, the other islands. What a beautiful blue the sea was, with it the sun sparkling on its surface: Everything was where it should be, gleaming and immaculate. Before us was a perfectly formed world.” They admired the view in silence and wondered what made it so beautiful and appealing. “Perhaps because we could see it all. Perhaps because if we fell off the edge we would die. Perhaps because nothing looks bad from a distance. Perhaps because we’d never seen it from this height.” I have a similar feeling every summer as we anticipate our annual sojourn on Monhegan Island, a small island roughly a mile and a half long and a half-mile wide situated twelve miles off the coast of Maine, in Muscongus Bay.

Like one of this year’s visits, many of our Monhegan adventures begin with a night’s stay at the Hotel Pemaquid beautifully situated adjacent to the Pemaquid Point lighthouse which appears on the verso of the Maine state quarter. We frequently stay here the night before our departure for the island because it is just a short drive to the New Harbor wharf where we catch the morning boat out to the island. From this lighthouse on its rocky prominence we can often see Monhegan shimmering on the horizon in the early evening light as our anticipation of our visit begins to grow. From there we can also see Outer Heron Island, the White Islands, and Damariscove Island to the southwest, all of which were British fishing outposts beginning in the early 17th century, as well as many of the other 70 or so islands that populate Muscongus Bay - Western and Eastern Egg Rock, the latter being the southernmost nesting area for the Atlantic Puffin; Franklin Island with its own lighthouse. Farther to the east are the Georges Islands, among them Thompson, McGee and Burnt Island; and Benner and Allen islands, which belong to the estate of the late Andrew Wyeth who painted there each summer until his death in January 2009. And there, farther out to sea, is solitary Monhegan Island. Charles Jenney, an early chronicler of the island’s history, called it “The Fortunate Isle.” I am fortunate to visit it as often as I do (three times this summer!). I can’t think of a better way to describe it. I look out at it and I am reminded of Pamuk’s essay . . . “Everything was where it should be.”

I have previously posted brief accounts of my earlier experiences on and impressions of Monhegan Island, but there are still some interesting details I would like to share with you. On past visits to the island I have had some delightful conversations with the island’s current historian who has been coming to Monhegan since she was a toddler over 80 summers ago, and she has filled me in on the island’s history far beyond anything I already knew. Our innkeeper at the Monhegan House, where we always stay when we are on the island, has been a wonderful source of information, anecdotes, and scuttlebutt as his family has also been associated with the island since the early 1920s, and he has been coming to the island since he was a kid. I have chatted with full-time islanders and those who have been coming for summers dating back almost fifty years. Also, I have done reading and studied records in the island library to fill in some of the empty places. Monhegan Island has a very rich history, far more than I can share with you here. But here are a few salient thoughts (random and otherwise) about this most fortunate of isles.

Monhegan is one of the very few permanently inhabited offshore islands in Maine. The English explorer John Smith, who first named this region “New England,” arrived in the island’s harbor in 1614 and archeological evidence on Manana, the small treeless and whale backed island which provides protection for the anchorage, suggests that seafarers of one sort or another have been on and around the island for at least a thousand years. Although fishermen have used the island as a base of operations for centuries, permanent settlement did not commence until circa 1780 with the arrival and residency of the Trefethren, Starling and Horn families. The earliest tombstone in the island cemetery on Lighthouse Hill belongs to an infant who was born and died on the island in 1784. A few homesteads and their out buildings were constructed along with several fish houses along the harbor’s rocky edges and its two small sand beaches. Several of these fish houses are still standing and in use in some fashion today. A village of sorts was beginning to take shape on the island as members of the three families began constructing new homes and farms. It followed no plan as it developed; its austere buildings arose where they proved to be most practical for their purpose. In December 1822, the Province of Maine separated from Massachusetts and joined the Union, although Monhegan was retained by the Commonwealth. The three original families purchased all of Massachusetts’ remaining island interests for $200 in July 1823 and the island was granted to the new State of Maine. The federal government appropriated money to construct a lighthouse in 1822 and the original tower was situated 175 feet above sea level. It was razed in 1850 and replaced with the current structure. The light was automated in 1960.

The island was established as a “Plantation” - an unincorporated community in Maine - in 1839 (later within Lincoln County) and its population began to grow in the mid 19th century as new families arrived and purchased parcels of land from the original owners. New houses and barns were constructed and by 1850 there were fifteen households on the island. An island school house was constructed in 1847 and the school, segregated by sex, was established the following year. Besides its use as a classroom, the school house has long hosted other island events such as dances, shows, lectures, and various public meetings.

The federal government purchased a small tract of land on neighboring Manana island and in 1855 a fog signal keeper’s house was erected and a 2500 pound hand-wrung bell was installed (the bell is now on the top of Lighthouse Hill). A foghorn was installed in 1870,and a steam whistle in 1876 to replace the horn. A new and improved horn was installed the following year to replace the whistle. A compressed air siren was finally installed in 1912. Today the lighthouse and the fog signal (also fully automated) are known by sailors and navigators up and down the coast of Maine.

Between 1850 and the 1870s the population of Monhegan grew from 72 to 185 residents and fishing and farming remained the major means of subsistence. A non-denominational community church was constructed in 1880 and the islanders were ministered to by visiting members of the cloth during the summer months. A minister from the mainland came one weekend each month during the winter, a practice that continues to this day.

The world beyond Muscongus Bay discovered Monhegan during the last quarter of the 19th century. In 1877, Sarah and Wilson Albee purchased half interest in a house formerly owned by the Trefethren family and opened the Albee House, the first boarding establishment on the island. It eventually became the current Monhegan House, the island’s first hotel. Life on Monhegan was changing. Most of the farms and pasture land fell into disuse by the turn of the century; there was little livestock left on the island and many of the few remaining barns began to disappear. The farmland and pastures were eventually reclaimed by dark spruce woodlands. Monhegan was nothing more than a small weather-beaten fishing village.

The late 19th century also signaled the genesis of a flourishing artist community on Monhegan. By 1890, the Albee House was popular with a growing number of artists while still others were taken in by island families. The English born and Boston-based artist and photographer S.P. Rolt Triscott and his student Sears Gallagher, a promising artist in his own right, arrived on the island in 1892 and stayed at the Albee House. Triscott returned again the next year and purchased a house not far from the Albee House and began a long relationship with Monhegan that lasted until his death on the island in 1925 (he is buried in the island cemetery). George Everett, another artist, came to live year round on the island in 1896 and turned speculator, purchasing island real estate from the locals and platting building lots on Horn’s Hill, on the village’s southern reach. Gallagher continued to summer on the island for the next six decades as more Boston artists followed in Triscott’s footsteps. Eric Hudson first noticed the island in 1897 while sailing up the Maine coast from Boston to Mount Desert Island farther Down East. He returned the following summer and built a cottage and continued to paint on the island. Soon artists from as far away as Philadelphia, New York and Boston were traveling by train to Maine and then catching a coastal steamer destined for Monhegan.

Robert Henri and members of the Ashcan School in New York City, known primarily for its urban realism, first came to the island in 1902 and they continued to make annual visits during the summer months. “It is a wonderful place to paint,” Henri writes. “So much in so small a place one could hardly believe it.” Now the artists focused their talents on Monhegan’s varied landscapes and the powerful seascapes that surrounded the island. The Old Lyme Colony painters from Connecticut arrived in 1908, staying at The Influence, one of the oldest surviving buildings on the island (circa 1820s). Soon other noted artists were associated with the island.

The artist Rockwell Kent first came to the island with Robert Henri. Finding Monhegan to be the “land of promise,” he subsequently purchased a piece of land platted by Everett and built a small cottage where he wintered on the island in 1906-1907. He built another cottage for his mother at Lobster Cove, on the southern end of the island, in 1908. Since April 1968 it has belonged to Jamie Wyeth who still comes to the island frequently to paint. (The Farnsworth Art Museum, in nearby Rockland, Maine, is featuring an exhibit this year focusing on Kent’s and Wyeth’s long association with Monhegan.) Kent, who continued to do manual labor and work on construction projects on the island, also built another small studio in the village in 1910 and operated a small art school there for a time. “Truly I loved that little world, Monhegan, “Kent wrote. “Small, sea-girt island that is was, a seeming floating speck in the infinitude of sea and sky . . . .” He also admired the islanders. “I envied them their strength, their knowledge of boats and their familiarity with that awesome portion of the infinite sea. I envied them their worker’s human dignity . . . .” The locals went about their work and left the artists and other visitors to tend to their own. Kent finally left Monhegan in 1953 and James Fitzgerald, an artist long connected with the area around Monterey, California, later used Kent’s cottage and studio into the early 1970s and painted some of his most interesting work there. One cannot think of Monhegan without conjuring up the works of Kent, Triscott, Gallagher, Henri, Fitzgerald, George Bellows, Edward Hopper, Reuben Tam, Andrew Winter and a host of other artists. Three generations of Wyeths have also painted on Monhegan.

By 1910 new summer cottages had been built by artists and others as the land of the original three families was being “gobbled up” by newcomers. By this time a second island hotel, the Island Inn, was established on a hillside facing the harbor and the wharf which still serves the island today. Kent described the two hotels as “big barn-like things, exteriorly as uninviting as their tasteless insides warranted. But what are we to expect, we touring picture painters and summer tourists and visitors - ‘rusticators’ - they call us. Don’t we invite just such monstrosities for our convenience? Don’t they, perhaps, match us?” Soon the summer community began to outnumber the permanent island inhabitants. The village was developing with the expansion of the unimproved roads (glorified paths actually), the establishment of a post office and regular mail service by boat from Port Clyde (originally known as Herring Gut), and the opening of various shops catering to the growing island population. Ice required for refrigeration of food was cut from a small island pond during the winter and stored in an adjacent ice house. The cutting and storage of ice continued until the early 1970s when electricity came to the island replacing gas and kerosene.

Many of the island residents, both permanent and summer rusticators, joined the visiting artists in celebrating the tercentenary of John Smith’s landing on the island, in 1914. This was the first golden era of life on Monhegan. Unfortunately, the advent of World War I that year brought this era to a quick end as life on the island returned to that of a relatively quiet and secluded fishing village throughout the war years. It did not remain so for long, however, and several new houses and cottages were constructed in the early 1920s. With a further increase of the postwar summer population came more work for the year round population of approximately 140 who kept themselves busy laying in more food and supplies and opening up and taking care of the summer cottages. More artists, such as Abraham Bogdanov and Mary Townsend Mason, frequented the island. A small village library was constructed and opened in 1930 and is still operated by a Library Association. Next to the village post office was “the Spa, a small soda fountain with a bingo parlor and recreation hall upstairs. Despite this new lease on life, new construction on the island slowed during the 1930s due to the long-term effects of the Great Depression.

The year-round population in 1940 had fallen to around 70, and this number dropped even lower during World War II when several eligible island men went into the military. Luckily all returned home safely although two were prisoners of war for a time. The island was on a war footing as the entire island was blacked out throughout the war and the Coast Guard patrolled the waters around the island and posted a sentry on the headlands on the eastern side of the island (the highest cliffs on the coast of Maine where I frequently go to “look toward Portugal”). Very little land was purchased during the war and there was almost no new construction of summer cottages.

Some new construction occurred on the island beginning in 1947 and life was returning to normal by 1950. Summer visitors were returning in increasing numbers and several artists began looking for or constructing cottages and studios. Monhegan also underwent an artists renaissance after the war. Andrew Winter, a native of Estonia who first came to Monhegan with Jay Connaway in the 1920s, returned to the island with his artist wife Mary, in 1940. Both lived and painted year round in a house near the island wharf until Andrew died in 1959 (his widow sold it in 1963). Like Rockwell Kent before him, Winter did odd jobs around the island and lobstered from his dory. It was also after the war that the new Monhegan House developed a close association with the Ashcan School in New York and hosted a number of artists visiting the island during the summer.

The years of postwar prosperity brought with them the possibility that the island might become the target of uncontrolled development and quickly outgrow its ability to sustain a way of life so many - the island’s permanent residents and summer visitors alike - had come to appreciate. To preserve the island’s unique character, Ted Edison, the son of Thomas Edison and a regular summer resident who is also buried on Lighthouse Hill, and a number of like-minded individuals established the Monhegan Associates, Inc., in 1954, to protect the island from over-development. It eventually purchased almost 500 acres of undeveloped land outside the village with the intention of maintaining its almost pristine natural state in perpetuity.

Today Monhegan Island remains much as it has been for many years. Once the summer residents and visitors leave in late September, the island is again a quiet fishing community. Unlike other lobstering operations along the coast of Maine, Monhegan’s lobstermen have chosen to fish only during the late fall and winter months, setting their traps with a great deal of ceremony on October 1 (until recently they waited until December 1), and finally pulling them for the season, typically at the end of June. While buyers do come to the island from time to time, there are no facilities for processing or marketing the catch on island and so it is transported to Port Clyde and Rockland, on the mainland. The rest of the year lobstermen find other pursuits to keep them busy. Island life in these northern climes always requires constant care and maintenance of the village buildings.

Come June the artists and summer people begin to return to the island to open their cottages and studios after a long winter off-island. Soon daily boats operating out of Port Clyde, New Harbor and Boothbay Harbor are docking at the wharf and disgorging flocks of daytrippers and others who have come to hike the island’s miles of nature paths, to paint and take photographs, or otherwise enjoy the peace and quiet of this secluded and most fortunate isle.

So, when I stand on the mainland and stare out at Monhegan Island, whether I plan to head out there the next day or not, I understand Pamuk when he describes the view from the rocky headland of Turkey’s Haybiliada Island. Everything does seem to be where it is supposed to be.

Sunday, September 23, 2012

The Longest Salute - Dispatches from Maine

Last week I was invited to present a lecture before the New Gloucester Historical Society to kick-off the fund-raising efforts for a new veterans monument to be located in Upper Gloucester village. I was honored to be asked to share these thoughts with my adopted hometown. What follows is the text of my remarks that evening in the town’s Meeting House.

What is the purpose of a veterans monument or memorial? I happen to live on the edge of our nation’s capital, a place that has its fair share of monuments and memorials to those Americans who served in the various branches of the armed forces, many of whom gave their last full measure of devotion to their country. There is the Vietnam War Memorial, that half buried black wedge etched with the names of thousands of men and women. Nearby, the Korean War Memorial with its larger-than life, cold steel combat patrol slogging toward the 38th Parallel and whatever fate awaited them. The long overdue memorial to those who served in World War II, that war to end all wars although we know, sadly, that this was not the case. Now that the last veteran of the Great War . . . World War I . . . has passed away, the nation is looking for a proper manner to recognize their wartime service. A bit too late? Some might think so. But not at all. It is never too late for that longest salute to all those who have served their country in times of war. And these monuments should not serve just as a memorial to those who died. We honor all those who served just as we celebrate all who returned home.

Spending the summer on the shores of Sabbathday Lake, right here in New Gloucester, I have read with great interest about the town’s efforts to properly recognize the almost 900 New Gloucester men and women veterans . . . going all the way back to the Revolutionary War, and right up to the present day . . . as well as the town’s long involvement in the military history of the United States. Since our visit last summer, the New Gloucester Historical Society, the Lunn- Hunnewell Amvets Post #6, and many other residents and business owners have expressed an interest in a Veterans Monument. With the very generous donation from Richard McCann and his family of land situated in Upper Gloucester village, the town now has an ideal location for an appropriate monument. I am pleased and honored to have been invited to speak here tonight to mark the kick-off to raise funds for the construction and long-term maintenance of the New Gloucester Veterans Monument.

It is important that each generation of citizens understands the sacrifices of the generations that came before. Those of us who have not experienced the dangers and deprivation of military service, whether it be in wartime or not, must try to better understand what others have endured in the defense of our nation.

Growing up I was always curious about my dad’s army service during World War II. I remember, as a kid, asking him. “Dad? What did you do during the war?” I imagine I was like many young boys my age when they first learned that their fathers had served in the military during World War II. My dad would occasionally share some of his war stories although I was perhaps too young to understand just what he was telling me, or just how painful these memories might have been for him. Sons look up to their fathers as heros. I did. That war was still fresh in many memories; it was not that many years earlier that Dad and his buddies, following the massive D-Day invasion, were slogging their way across northern France in late 1944, slowly pushing the Germans back to their own border. Dad never really went into many details about the war, or exactly what he did, but there were a few stories he shared, and I still remember them as clearly now as the day he first told them to me.

Perhaps the most vivid of these, the one that still stands out in my own recollections of my childhood, was Dad’s participation in the Battle of the Bulge, the Ardennes campaign, the greatest land battle ever fought by the military forces of the United States between December 16, 1944 and January 25, 1945. This great battle halted the final Nazi juggernaut to defeat the Allies and turned the tide of war against the Germans who would surrender just six months later.

I have been thinking of these stories more recently, especially after Dad passed away almost three years ago. Dad had served in General George Patton’s Third Army during the northern European campaign, in 1944-1945. Not long ago I visited my dad’s grave for the first time since his memorial service at the Florida National Cemetery. It was my first opportunity to see the inscription on the marble tablet marking the niche containing his ashes. It was then and there that I learned for the very first time, and much to my complete surprise, that Dad had received the Bronze Star, the fourth highest decoration awarded for distinguished, heroic or meritorious achievement or service in combat. He really was a hero even if not that many people, including his son, knew it.

A few days later my wife and I visited with one of the last surviving members of Dad’s unit. I first learned about Harry a few years ago when I was doing some online research on the Ardennes region of eastern Belgium and Luxembourg. I came across a photo essay on the area by a veteran of the Battle of the Bulge who had returned to visit the places he knew from the war. Many of the places and events he described seemed very similar to the ones my dad had told me about when I was a kid. I called Dad up and asked him whether he knew the guy who had posted the photos. “Why sure,” he said.” Harry was one of my closest buddies during the war.” They had not seen each other since the early days of 1945, in the immediate wake of the battle, and, as it turned out, they lived only a few miles apart in Florida. Dad gave Harry a call and over the next few months they renewed their old friendship. Harry and I also exchanged occasional notes and we planned to meet when my travels took me to Florida. I regret that I was not able to meet with Harry when Dad was still alive, but over lunch I told his old army buddy what I knew of Dad’s wartime exploits and Harry was able to fill me in on many more details. He answered a lot of questions I had about that chapter of my dad’s life.

I am sure my dad’s story is like those of many others who were called to serve their country in a time of war . . . like many of the almost 900 individuals whose names will eventually appear on the New Gloucester Veterans Monument. Dad was drafted into the US Army in early 1943, just a couple months shy of his 19th birthday. He left his native Michigan and did his basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, where he was eventually assigned to the 104th Infantry Regiment of the 26th Infantry (Yankee) Division. This division was originally formed out of Massachusetts National Guard units for service in World War I as part of the Allied Expeditionary Force, and the division and regiment have had a long and distinguished history. In World War I, the 104th became the first US Army regiment to receive the fourragère of the French Croix de Guerre after showing “fortitude et courage” in repelling a German attack at Aprémont on April 10-13, 1918. These words have been the regiment’s motto ever since. Dad underwent training at Fort Jackson, and later at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and participated in maneuvers in Tennessee the winter of 1943/1944.

Departing Fort Jackson, in August 1944, upon completion of basic combat training, Dad and Harry and their unit were sent to the huge Camp Shanks - “Last Stop USA” - in New York’s Hudson Valley. It was time to go to war. Dad would serve until his discharge in early January 1946 and he and Harry and their buddies would grow up fast in those years of hardship not knowing if they would survive. A lot of the brave men who went to war never came home. Dad and Harry were lucky.

After Camp Shanks the 26th Infantry Division embarked from Fort Miles Standish, at Boston, in late August 1944, crossing the Atlantic directly to Cherbourg, France where it landed on September 7, 1944, some three months after D-Day. The division was first attached to III Corps, Ninth Army at the Valognes staging area where it underwent extensive combat training and was assigned to local security duties along the Cherbourg peninsula and the Normandy beachheads used on D-Day.

Following this training, the 26th Infantry Division was assigned in October 1944 to XII Corps in General George Patton’s Third Army which moved so quickly across northern France that it soon out distanced its supply line and had to slow down its advance. The 26th Division departed Normandy and caught up with Third Army in its operational area in the Lorraine region in northeastern France, the same area where the division and the 104th Regiment had served with distinction in World War I. There it took up a defensive position on Third Army’s right flank near Salonnes. It was here Dad and his 104th Infantry Regiment had their baptism under fire in an action against the German 11th Panzer Division in the Moncourt Woods, in late October 1944. This is where all the combat training paid off as these green American soldiers went up against a seasoned German division which had been in combat since 1940 and saw action in the Balkans and along the Eastern Front before it was sent to France in early 1944.

During that first week of November 1944, Third Army prepared to launch a large-scale offensive along the front near the German border. The first major offensive action by the 26th Infantry Division was against German positions in and around Vic-sur-Seille on November 8. The 104th Regiment advanced on the left flank toward Hampont and the Houbange Woods, and it captured Bennestroft two days later. The regiment proved it was up to the task assigned to it and it added a second regimental Croix de Guerre to its colors.

The division continued to advance on the German border in late November with the 104th Regiment crossing the Canal du Rhin au Marne on December 1. A few days later the regiment reached the Maginot Line, a system of concrete fortifications constructed by the French near the border with Germany after World War I. There the regiment launched an attack against heavy German resistance as part of Third Army’s planned assault into Germany.

Following this assault, Dad’s regiment was transported to a rear area near Metz, in France, for some much needed R&R. But there was no rest for the weary. During the early morning hours of December 16, the Germans launched a surprise major counteroffensive through the Ardennes of Luxembourg and eastern Belgium in a last ditch effort to divide American and British forces advancing toward Germany. The Germans quickly advanced westward creating a large “bulge” in the Allied lines while never actually breaking out. Third Army was forced to suspend its offensive in the Saar Basin and reposition its forces in order to address this new German aggression. All units of Third Army were thrown against the southern shoulder of the German bulge into the Allied lines. The 26th Infantry Division, was transported from Metz to the vicinity of Arlon, in southeastern Belgium, in mid December 1944 where it launched an assault northward through western Luxembourg to help relieve American forces under siege at Bastogne, Belgium.

By December 23 the 104th was advancing through the hills and gorges of the Ardennes toward the Sûre (Saar) River and it met heavy Germany resistance throughout December 24 and on Christmas day as it continued to advance. There was intense combat on Christmas morning as the 104th moved up to Esch-sur-Sûre to establish important bridgeheads over the Sûre. The remainder of the division continued its northward advance in the closing days of 1944 in an effort to break the German siege of Bastogne. Dad and his unit remained in Esch-sur-Sûre for several day securing the bridgeheads and its regimental headquarters. It was here that Dad won his Bronze Star.

Heavy snow and German resistance stalled the American advance in early January 1945 and the 26th Division remained in northeastern Luxembourg and eastern Belgium for almost a month, until the German offensive had all but collapsed. By January 25, 1945 the German counteroffensive through the Ardennes was over and Third Army resumed its eastward advance from northern Luxembourg into Germany. Never able to enjoy their relief from front line action, the 26th Infantry Division had finally made it into Germany and it would not leave until the job it was given was completed.

By early March 1945 when it resumed the offensive, Third Army was already well on its way to the Rhine River and the heartland of Germany against scattered yet heavy enemy resistance. Once it crossed the Rhine in late March, resistance diminished and the division advanced quickly south of Frankfurt to the bridgeheads over the Main River east of that city. On April 15 the entire division was approximately 10 miles from the Czechoslovakian border in southeastern Germany where its advance was intentionally halted.

It was here that the war took on an entirely different meaning for Dad and his buddies. Perhaps they did not realize it at the time. One expects to encounter death and destruction when engaged in combat. But it was there, in the final weeks of the war, that death and the cruelties of war took on a different and more sinister dimension. The XII Corps of Third Army, including the 26th Infantry Division, was tasked with the pacification of eastern Bavaria, and it quickly advanced southward toward the Danube River and the Austro-German border near Passau. The division moved into Austria in early May and elements of the division took Linz on May 4. On the following day divisional units overran the Gusen concentration camp, part of the Mauthausen camp complex, east of Linz, and on May 6 it continued north into Czechoslovakia. Third Army had moved farther east than any other American unit in the European theater. This is a part of the war my dad never told me about. It was at Gusen that young American soldiers witnessed man’s inhumanity toward man up close and personal. Even years later, when I was spending my professional career investigating and prosecuting the perpetrators of Nazi war crimes and atrocities, my dad never told me about this part of the war. I wish he had, but I understand why he didn’t.

Germany surrendered unconditionally on May 7 and hostilities officially ended on May 9. The following day elements of the 26th Infantry Division made contact with advanced units of the Soviet Red Army in the vicinity of Ceske-Budejovice, Czechoslovakia. Since the autumn of 1944 the 26th Infantry Division had been in combat for 210 days; the 104th for 177 days. But the war was not over; the 26th and the 104th returned to the area around Linz to train for eventual deployment in the Pacific. Luckily the war ended there before they had to go and finish the work begun in the forest and hills of northeastern France almost a year earlier.

When I was attending university in Germany in 1971-1972 I had an opportunity to visit many of the places where the Yankee Division and the 104th Infantry regiment had served with distinction. During the war Dad had plotted the movements of his unit on various maps he had found along the way. He had also kept a small journal in his boot and I had all of these with me during my time in Europe. One of my German friends took a great interest in what I was doing and I told him the stories my dad had shared with me as a kid about his wartime service in Patton’s Third Army. It was then that Johannes told me that his own father had served in the 11th Panzer Division, the elite German unit my dad’s regiment first faced off against in northeastern France. We talked and it turned out the stories his father told him were very familiar to the ones I had heard as a boy. Twenty-five years earlier two young men . . . boys actually . . . one American, the other German, stared down the length of their rifles at each other. Years later their son had become friends. I met Johannes’ father. I’m pretty sure he and Dad could have been friends in another time and place.

I spent quite a bit of time in the area of northeastern France, visited the Moncourt Woods where Dad first saw combat, and then traveled throughout the Ardennes looking for the various places Dad had told me about. Recalling some of the more vivid stories about his time in Esch-sur-Sûre, I visited the town several times. On one visit I managed to identify the house in the rue de l’eglise where Dad and his buddies had bunked during that snowy Yuletide back in 1944. I knocked on the door to discover that the family to whom the house belonged during the war, still lived there and they gave me a tour and invited me to stay for coffee and cake. Later that evening I had dinner at the Hotel Ardennes, which had served as the regimental headquarters during the late stage of the Ardennes offensive. When I told the waiter why I was there, he brought me a bottle of wine and my entire dinner was on the house. The American liberators were still looked upon as heros. And so were their sons, apparently. I can’t think of a time I was prouder to be an American. Or for what my dad and his buddies had done years ago.

So it was a real treat to finally meet Harry only wishing that Dad had lived long enough to share that day with us. While Dad never really involved himself in veteran affairs and unit reunions after the war, Harry jumped in with both feet and even today, at age 89, he works hard to make sure younger generations never forget what he and Dad and so many like them did to preserve our way of life in this country. We remember and salute them all.

So why have I told you all of this? In Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Act 2, Scene I, we are told that “what is past is prologue.” We learn from the past. Time is long and therefore memories must be long to recall what has come before and its importance to what happens now and in the future. Just as it is important to remember the stories my dad told me about the war, and those that I learned about after he had passed away, it is important that all of us remember the stories we have been told. The names that will appear on the New Gloucester Veterans Monument will be fresh in the memories of some. Others less so, and some have been long forgotten. But not any more. Their names will now be engraved for present and future generations to see and reflect on. What happened to these people in times of war? We might not recall the details of their particular service. What they saw. What they did. But we should never forget their names. Never. The new Veterans Monument will stand as the longest salute to these honored men and women. Recall the words of Abraham Lincoln:

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us -- that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion -- that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain -- that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom -- and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

What is the purpose of a veterans monument or memorial? I happen to live on the edge of our nation’s capital, a place that has its fair share of monuments and memorials to those Americans who served in the various branches of the armed forces, many of whom gave their last full measure of devotion to their country. There is the Vietnam War Memorial, that half buried black wedge etched with the names of thousands of men and women. Nearby, the Korean War Memorial with its larger-than life, cold steel combat patrol slogging toward the 38th Parallel and whatever fate awaited them. The long overdue memorial to those who served in World War II, that war to end all wars although we know, sadly, that this was not the case. Now that the last veteran of the Great War . . . World War I . . . has passed away, the nation is looking for a proper manner to recognize their wartime service. A bit too late? Some might think so. But not at all. It is never too late for that longest salute to all those who have served their country in times of war. And these monuments should not serve just as a memorial to those who died. We honor all those who served just as we celebrate all who returned home.

Spending the summer on the shores of Sabbathday Lake, right here in New Gloucester, I have read with great interest about the town’s efforts to properly recognize the almost 900 New Gloucester men and women veterans . . . going all the way back to the Revolutionary War, and right up to the present day . . . as well as the town’s long involvement in the military history of the United States. Since our visit last summer, the New Gloucester Historical Society, the Lunn- Hunnewell Amvets Post #6, and many other residents and business owners have expressed an interest in a Veterans Monument. With the very generous donation from Richard McCann and his family of land situated in Upper Gloucester village, the town now has an ideal location for an appropriate monument. I am pleased and honored to have been invited to speak here tonight to mark the kick-off to raise funds for the construction and long-term maintenance of the New Gloucester Veterans Monument.

It is important that each generation of citizens understands the sacrifices of the generations that came before. Those of us who have not experienced the dangers and deprivation of military service, whether it be in wartime or not, must try to better understand what others have endured in the defense of our nation.

Growing up I was always curious about my dad’s army service during World War II. I remember, as a kid, asking him. “Dad? What did you do during the war?” I imagine I was like many young boys my age when they first learned that their fathers had served in the military during World War II. My dad would occasionally share some of his war stories although I was perhaps too young to understand just what he was telling me, or just how painful these memories might have been for him. Sons look up to their fathers as heros. I did. That war was still fresh in many memories; it was not that many years earlier that Dad and his buddies, following the massive D-Day invasion, were slogging their way across northern France in late 1944, slowly pushing the Germans back to their own border. Dad never really went into many details about the war, or exactly what he did, but there were a few stories he shared, and I still remember them as clearly now as the day he first told them to me.

Perhaps the most vivid of these, the one that still stands out in my own recollections of my childhood, was Dad’s participation in the Battle of the Bulge, the Ardennes campaign, the greatest land battle ever fought by the military forces of the United States between December 16, 1944 and January 25, 1945. This great battle halted the final Nazi juggernaut to defeat the Allies and turned the tide of war against the Germans who would surrender just six months later.

I have been thinking of these stories more recently, especially after Dad passed away almost three years ago. Dad had served in General George Patton’s Third Army during the northern European campaign, in 1944-1945. Not long ago I visited my dad’s grave for the first time since his memorial service at the Florida National Cemetery. It was my first opportunity to see the inscription on the marble tablet marking the niche containing his ashes. It was then and there that I learned for the very first time, and much to my complete surprise, that Dad had received the Bronze Star, the fourth highest decoration awarded for distinguished, heroic or meritorious achievement or service in combat. He really was a hero even if not that many people, including his son, knew it.

A few days later my wife and I visited with one of the last surviving members of Dad’s unit. I first learned about Harry a few years ago when I was doing some online research on the Ardennes region of eastern Belgium and Luxembourg. I came across a photo essay on the area by a veteran of the Battle of the Bulge who had returned to visit the places he knew from the war. Many of the places and events he described seemed very similar to the ones my dad had told me about when I was a kid. I called Dad up and asked him whether he knew the guy who had posted the photos. “Why sure,” he said.” Harry was one of my closest buddies during the war.” They had not seen each other since the early days of 1945, in the immediate wake of the battle, and, as it turned out, they lived only a few miles apart in Florida. Dad gave Harry a call and over the next few months they renewed their old friendship. Harry and I also exchanged occasional notes and we planned to meet when my travels took me to Florida. I regret that I was not able to meet with Harry when Dad was still alive, but over lunch I told his old army buddy what I knew of Dad’s wartime exploits and Harry was able to fill me in on many more details. He answered a lot of questions I had about that chapter of my dad’s life.

I am sure my dad’s story is like those of many others who were called to serve their country in a time of war . . . like many of the almost 900 individuals whose names will eventually appear on the New Gloucester Veterans Monument. Dad was drafted into the US Army in early 1943, just a couple months shy of his 19th birthday. He left his native Michigan and did his basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, where he was eventually assigned to the 104th Infantry Regiment of the 26th Infantry (Yankee) Division. This division was originally formed out of Massachusetts National Guard units for service in World War I as part of the Allied Expeditionary Force, and the division and regiment have had a long and distinguished history. In World War I, the 104th became the first US Army regiment to receive the fourragère of the French Croix de Guerre after showing “fortitude et courage” in repelling a German attack at Aprémont on April 10-13, 1918. These words have been the regiment’s motto ever since. Dad underwent training at Fort Jackson, and later at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and participated in maneuvers in Tennessee the winter of 1943/1944.

Departing Fort Jackson, in August 1944, upon completion of basic combat training, Dad and Harry and their unit were sent to the huge Camp Shanks - “Last Stop USA” - in New York’s Hudson Valley. It was time to go to war. Dad would serve until his discharge in early January 1946 and he and Harry and their buddies would grow up fast in those years of hardship not knowing if they would survive. A lot of the brave men who went to war never came home. Dad and Harry were lucky.

After Camp Shanks the 26th Infantry Division embarked from Fort Miles Standish, at Boston, in late August 1944, crossing the Atlantic directly to Cherbourg, France where it landed on September 7, 1944, some three months after D-Day. The division was first attached to III Corps, Ninth Army at the Valognes staging area where it underwent extensive combat training and was assigned to local security duties along the Cherbourg peninsula and the Normandy beachheads used on D-Day.

Following this training, the 26th Infantry Division was assigned in October 1944 to XII Corps in General George Patton’s Third Army which moved so quickly across northern France that it soon out distanced its supply line and had to slow down its advance. The 26th Division departed Normandy and caught up with Third Army in its operational area in the Lorraine region in northeastern France, the same area where the division and the 104th Regiment had served with distinction in World War I. There it took up a defensive position on Third Army’s right flank near Salonnes. It was here Dad and his 104th Infantry Regiment had their baptism under fire in an action against the German 11th Panzer Division in the Moncourt Woods, in late October 1944. This is where all the combat training paid off as these green American soldiers went up against a seasoned German division which had been in combat since 1940 and saw action in the Balkans and along the Eastern Front before it was sent to France in early 1944.

During that first week of November 1944, Third Army prepared to launch a large-scale offensive along the front near the German border. The first major offensive action by the 26th Infantry Division was against German positions in and around Vic-sur-Seille on November 8. The 104th Regiment advanced on the left flank toward Hampont and the Houbange Woods, and it captured Bennestroft two days later. The regiment proved it was up to the task assigned to it and it added a second regimental Croix de Guerre to its colors.

The division continued to advance on the German border in late November with the 104th Regiment crossing the Canal du Rhin au Marne on December 1. A few days later the regiment reached the Maginot Line, a system of concrete fortifications constructed by the French near the border with Germany after World War I. There the regiment launched an attack against heavy German resistance as part of Third Army’s planned assault into Germany.

Following this assault, Dad’s regiment was transported to a rear area near Metz, in France, for some much needed R&R. But there was no rest for the weary. During the early morning hours of December 16, the Germans launched a surprise major counteroffensive through the Ardennes of Luxembourg and eastern Belgium in a last ditch effort to divide American and British forces advancing toward Germany. The Germans quickly advanced westward creating a large “bulge” in the Allied lines while never actually breaking out. Third Army was forced to suspend its offensive in the Saar Basin and reposition its forces in order to address this new German aggression. All units of Third Army were thrown against the southern shoulder of the German bulge into the Allied lines. The 26th Infantry Division, was transported from Metz to the vicinity of Arlon, in southeastern Belgium, in mid December 1944 where it launched an assault northward through western Luxembourg to help relieve American forces under siege at Bastogne, Belgium.

By December 23 the 104th was advancing through the hills and gorges of the Ardennes toward the Sûre (Saar) River and it met heavy Germany resistance throughout December 24 and on Christmas day as it continued to advance. There was intense combat on Christmas morning as the 104th moved up to Esch-sur-Sûre to establish important bridgeheads over the Sûre. The remainder of the division continued its northward advance in the closing days of 1944 in an effort to break the German siege of Bastogne. Dad and his unit remained in Esch-sur-Sûre for several day securing the bridgeheads and its regimental headquarters. It was here that Dad won his Bronze Star.

Heavy snow and German resistance stalled the American advance in early January 1945 and the 26th Division remained in northeastern Luxembourg and eastern Belgium for almost a month, until the German offensive had all but collapsed. By January 25, 1945 the German counteroffensive through the Ardennes was over and Third Army resumed its eastward advance from northern Luxembourg into Germany. Never able to enjoy their relief from front line action, the 26th Infantry Division had finally made it into Germany and it would not leave until the job it was given was completed.

By early March 1945 when it resumed the offensive, Third Army was already well on its way to the Rhine River and the heartland of Germany against scattered yet heavy enemy resistance. Once it crossed the Rhine in late March, resistance diminished and the division advanced quickly south of Frankfurt to the bridgeheads over the Main River east of that city. On April 15 the entire division was approximately 10 miles from the Czechoslovakian border in southeastern Germany where its advance was intentionally halted.

It was here that the war took on an entirely different meaning for Dad and his buddies. Perhaps they did not realize it at the time. One expects to encounter death and destruction when engaged in combat. But it was there, in the final weeks of the war, that death and the cruelties of war took on a different and more sinister dimension. The XII Corps of Third Army, including the 26th Infantry Division, was tasked with the pacification of eastern Bavaria, and it quickly advanced southward toward the Danube River and the Austro-German border near Passau. The division moved into Austria in early May and elements of the division took Linz on May 4. On the following day divisional units overran the Gusen concentration camp, part of the Mauthausen camp complex, east of Linz, and on May 6 it continued north into Czechoslovakia. Third Army had moved farther east than any other American unit in the European theater. This is a part of the war my dad never told me about. It was at Gusen that young American soldiers witnessed man’s inhumanity toward man up close and personal. Even years later, when I was spending my professional career investigating and prosecuting the perpetrators of Nazi war crimes and atrocities, my dad never told me about this part of the war. I wish he had, but I understand why he didn’t.

Germany surrendered unconditionally on May 7 and hostilities officially ended on May 9. The following day elements of the 26th Infantry Division made contact with advanced units of the Soviet Red Army in the vicinity of Ceske-Budejovice, Czechoslovakia. Since the autumn of 1944 the 26th Infantry Division had been in combat for 210 days; the 104th for 177 days. But the war was not over; the 26th and the 104th returned to the area around Linz to train for eventual deployment in the Pacific. Luckily the war ended there before they had to go and finish the work begun in the forest and hills of northeastern France almost a year earlier.

When I was attending university in Germany in 1971-1972 I had an opportunity to visit many of the places where the Yankee Division and the 104th Infantry regiment had served with distinction. During the war Dad had plotted the movements of his unit on various maps he had found along the way. He had also kept a small journal in his boot and I had all of these with me during my time in Europe. One of my German friends took a great interest in what I was doing and I told him the stories my dad had shared with me as a kid about his wartime service in Patton’s Third Army. It was then that Johannes told me that his own father had served in the 11th Panzer Division, the elite German unit my dad’s regiment first faced off against in northeastern France. We talked and it turned out the stories his father told him were very familiar to the ones I had heard as a boy. Twenty-five years earlier two young men . . . boys actually . . . one American, the other German, stared down the length of their rifles at each other. Years later their son had become friends. I met Johannes’ father. I’m pretty sure he and Dad could have been friends in another time and place.

I spent quite a bit of time in the area of northeastern France, visited the Moncourt Woods where Dad first saw combat, and then traveled throughout the Ardennes looking for the various places Dad had told me about. Recalling some of the more vivid stories about his time in Esch-sur-Sûre, I visited the town several times. On one visit I managed to identify the house in the rue de l’eglise where Dad and his buddies had bunked during that snowy Yuletide back in 1944. I knocked on the door to discover that the family to whom the house belonged during the war, still lived there and they gave me a tour and invited me to stay for coffee and cake. Later that evening I had dinner at the Hotel Ardennes, which had served as the regimental headquarters during the late stage of the Ardennes offensive. When I told the waiter why I was there, he brought me a bottle of wine and my entire dinner was on the house. The American liberators were still looked upon as heros. And so were their sons, apparently. I can’t think of a time I was prouder to be an American. Or for what my dad and his buddies had done years ago.

So it was a real treat to finally meet Harry only wishing that Dad had lived long enough to share that day with us. While Dad never really involved himself in veteran affairs and unit reunions after the war, Harry jumped in with both feet and even today, at age 89, he works hard to make sure younger generations never forget what he and Dad and so many like them did to preserve our way of life in this country. We remember and salute them all.

So why have I told you all of this? In Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Act 2, Scene I, we are told that “what is past is prologue.” We learn from the past. Time is long and therefore memories must be long to recall what has come before and its importance to what happens now and in the future. Just as it is important to remember the stories my dad told me about the war, and those that I learned about after he had passed away, it is important that all of us remember the stories we have been told. The names that will appear on the New Gloucester Veterans Monument will be fresh in the memories of some. Others less so, and some have been long forgotten. But not any more. Their names will now be engraved for present and future generations to see and reflect on. What happened to these people in times of war? We might not recall the details of their particular service. What they saw. What they did. But we should never forget their names. Never. The new Veterans Monument will stand as the longest salute to these honored men and women. Recall the words of Abraham Lincoln:

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us -- that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion -- that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain -- that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom -- and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Thursday, September 20, 2012

A Small Town Library - Dispatches from Maine

There is something very special about a small town library. Living as I do in the Washington, DC metropolitan area, I am in a habit of frequenting large and often very impersonal libraries. For years I have wandered the cavernous reading rooms and the labyrinthine stacks of the Library of Congress. Then there are the many university libraries, the District of Columbia Public Library system, as well as those serving the suburban counties in Maryland and Virginia. During the summer I frequent the campus library at Bates College, in Lewiston, Maine, where I have research and borrowing privileges so that I can work on my various projects while we are on our summer hiatus. In most of these libraries you pretty much need to know what you are looking for and how to find it. These institutions are manned by librarians and their acolytes and they are often pulled in so many directions that there is little opportunity for personal attention and consultation. There are, of course, exceptions to every rule, and I have found individuals who are ready and willing to assist me. More times than not, however, I am left to fend for myself. And usually I prefer it that way. So a small town library is a welcome respite from the routine and one to be savored.

A couple of years ago we finally discovered the village library serving New Gloucester, Maine, where we have spent our summers for the past 25 years. I don’t know why we did not visit it before since we use our summer sojourns at the lake to catch up on our reading. Early on these visits were for two or three weeks each summer and we usually brought enough reading material with us to keep us busy. Three summers ago, after my retirement, we began to spend the entire summer at the lake and we soon ran out of books to read. Good book stores can be few and far between up here (although there are some we do like to frequent) and so we decided to check out the local library to see if we could borrow books over the summer. We were delighted when we learned that we could, and even more delighted when we discovered it to be an absolutely charming place staffed by some absolutely charming people who have also become our friends and whom we look forward to seeing whenever we return to Maine.

One of the more charming and inviting aspects of the library is its location. It is situated on the Intervale Road in the heart of New Gloucester’s “Lower Village and adjacent to the Town Hall and Meeting House, and just around the corner from the large white-washed Congregational Church. It is housed in the former high school constructed in 1903 and closed in 1962 when the high schools in New Gloucester and neighboring Gray merged. The library, formerly housed in the town meeting hall, moved into the vacant building in 1998.

And then there are the people. We have come to know Suzan Hawkins and Carla Mcallister, the two librarians who always meet you with a big smile and a pleasant “hello.” They seem to know the names of everyone who visits the library and probably do. Everyone feels most welcome be they young or old. There is always something interesting to look at and usually one of the tables has a puzzle at some stage of completion.

A small town library is often the hub of the community, and this is certainly the case here in New Gloucester. It sponsors an annual challenge to see how many books its patrons can read over the summer. A small stone is placed into a large glass jar as each book is completed. This year the jar contained over 5000 stones when the challenge ended in late August, a sizeable increase over previous years. There is the annual pet show, book groups, a reading hour for the kids, and much, much more. It is just a great place to hang out. You feel the pulse of the community strong and clear when you visit.

This year I was honored to be part of what we hope will become an annual event . . . “Poetry in the Gazebo.” Earlier this past week those of us interested in sharing our work as well as our favorite poems by others gathered in the charming little gazebo behind the library. It was a cool evening signaling the approach of autumn. The trees were showing hints of color and what better way to celebrate poetry? We always hate to leave Maine and one of the things we miss most is the friendly folks and atmosphere at the New Gloucester Library. There is always next summer. It can’t come soon enough.

A couple of years ago we finally discovered the village library serving New Gloucester, Maine, where we have spent our summers for the past 25 years. I don’t know why we did not visit it before since we use our summer sojourns at the lake to catch up on our reading. Early on these visits were for two or three weeks each summer and we usually brought enough reading material with us to keep us busy. Three summers ago, after my retirement, we began to spend the entire summer at the lake and we soon ran out of books to read. Good book stores can be few and far between up here (although there are some we do like to frequent) and so we decided to check out the local library to see if we could borrow books over the summer. We were delighted when we learned that we could, and even more delighted when we discovered it to be an absolutely charming place staffed by some absolutely charming people who have also become our friends and whom we look forward to seeing whenever we return to Maine.

One of the more charming and inviting aspects of the library is its location. It is situated on the Intervale Road in the heart of New Gloucester’s “Lower Village and adjacent to the Town Hall and Meeting House, and just around the corner from the large white-washed Congregational Church. It is housed in the former high school constructed in 1903 and closed in 1962 when the high schools in New Gloucester and neighboring Gray merged. The library, formerly housed in the town meeting hall, moved into the vacant building in 1998.

And then there are the people. We have come to know Suzan Hawkins and Carla Mcallister, the two librarians who always meet you with a big smile and a pleasant “hello.” They seem to know the names of everyone who visits the library and probably do. Everyone feels most welcome be they young or old. There is always something interesting to look at and usually one of the tables has a puzzle at some stage of completion.

A small town library is often the hub of the community, and this is certainly the case here in New Gloucester. It sponsors an annual challenge to see how many books its patrons can read over the summer. A small stone is placed into a large glass jar as each book is completed. This year the jar contained over 5000 stones when the challenge ended in late August, a sizeable increase over previous years. There is the annual pet show, book groups, a reading hour for the kids, and much, much more. It is just a great place to hang out. You feel the pulse of the community strong and clear when you visit.

This year I was honored to be part of what we hope will become an annual event . . . “Poetry in the Gazebo.” Earlier this past week those of us interested in sharing our work as well as our favorite poems by others gathered in the charming little gazebo behind the library. It was a cool evening signaling the approach of autumn. The trees were showing hints of color and what better way to celebrate poetry? We always hate to leave Maine and one of the things we miss most is the friendly folks and atmosphere at the New Gloucester Library. There is always next summer. It can’t come soon enough.

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

65,000 Hits As of Today!!

Thanks to everyone worldwide who has visited Looking Toward Portugal since December 2008. This project has been more successful than I could have ever imagined when I first started out. I hope you have enjoyed the "Dispatches from Maine" which I have been posting over the past couple of months and that you will continue to look in from time to time for more random notes from the edge of America. Better yet, become a follower.

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

It All Seems So Long Ago - Dispatch from New Hampshire

Dateline: Pittsburg, New Hampshire

Today marks the eleventh anniversary of the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, and the crash of a fourth hijacked commercial airliner in rural Pennsylvania. Everyone of a certain age can remember where they were that Tuesday morning, a date and event that is simply known as “9/11.” You say it, and everyone knows what you mean.

I remember that morning like it was yesterday. We were at the lake in Maine for much of August 2001, returning home to our suburban home on the edge of Washington, DC just three weeks before that portentous date. I was still gradually settling back into my routines at home and work, hoping to hold on to the lake’s serenity as long as possible.

That morning I arose from bed around 6am hoping to get a little writing done before it was time to shower and dress and begin making my way to my office in downtown Washington. It was a beautiful late summer day, a gentle breeze and the sky a robin egg blue. I walked the block to the bus stop and shortly thereafter I was sitting on the Metro for the short ride into the center of the city. People were reading newspapers and magazines while others stared vacantly forward or out the window at the urban landscape before we dipped underground at Union Station. It was an ordinary morning commute in every way.

Leaving the station and taking the escalators to the street level I stopped at the local deli for a cup of coffee and within a few minutes I was at my desk and looking through what I had to do that day. I walked to the other side of our suite of offices to check my mail when I realized that I was the only one around. The usual hallway traffic was strangely absent and no one seemed to be in their office. As I passed by our conference room I was surprised to find most of my colleagues sitting around the table. We never had meetings this early in the day. Had I missed something?

I walked in and nobody seemed to notice my arrival; everyone’s eyes were focused on a CNN reporter on the television. “What is going on?” I inquired. “Apparently a plane has crashed into the World Trade Center,” came the reply. I sat down and watched as a thick column of black smoke rose from the upper stories of one of the towers. The information was sketchy at that time. Was it a plane? What kind of a plane was it? Big? Small? The newscasts on all the channels were saying pretty much the same thing. It was only speculation. In the meantime there were televised scenes of New York City’s emergency response teams - the police and fire department - arriving at the plaza at the base of the towers. As we watched we were suddenly horrified to see a large commercial jet fly directly into the mid-section of the second tower followed by a large, fiery explosion and a shower of debris onto the streets below. Suddenly the speculation came to an abrupt end. What we were watching was an intentional attack on the United States. But who was responsible? Shortly thereafter we heard a very large plane pass directly over our building and a few minutes later the television was showing smoke and fire at the Pentagon. Another plane had crashed there. Soon the cry of sirens could be heard and fleets of police cars and fire trucks began to move through the downtown streets of Washington. I walked outside and I could see the smoke from the Pentagon as it gradually dissipated into the blue, late summer sky. Fighter jets and helicopters were flying low over the city. I returned to the conference room in time to see the twin towers collapse into piles of wreckage and clouds of dust and debris over lower Manhattan. Fires raged at the Pentagon.

What followed seemed at the time like an eternity of confusion. The radio and television broadcasts were full of guessing and wild speculation. There were reports of bombs going off around Washington, that more hijacked planes were heading toward targets in the city. The Capitol . . . the White House only two three blocks from my office; I could see the flag waving from its roof. Suddenly more police cars were everywhere you looked. Soldiers in Humvees cruised up and down the streets just below my office window. What should we do? Should we stay where we were? Should we go somewhere, and if so, where? All we knew was that something very terrible was happening all around us. Finally came the word to evacuate. Get as far away from downtown as possible. I threw a few things in my bag and called home to tell Sally Ann I was safe and walking out of the city. I locked my office and joined the multitude as we flooded out of Washington on every compass heading, keeping our eyes on the sky and calling friends and family on cell phones to assure them we were safe . . . or were we? We still had no idea what was happening. I recall that there was very little talking; nobody really knew what to say each other. Once I got far enough away from downtown I called Sally Ann and she drove down to pick me up and take me the rest of the way home. Neighbors gathered to watch the television in disbelief as the details of that morning gradually came to light. And we have been living with the consequences of those heinous acts for over a decade.

This morning I am sitting in a rustic lodge at the rooftop of New Hampshire. Those events of eleven years ago seem so long ago and so far away and remote from the tranquility of this peaceful locale. But as far away as we can get from both that place and time, we shall never forget what happened on that date that will be forever seared into on our consciousness. Live for the future, but never forget the past.

Today marks the eleventh anniversary of the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, and the crash of a fourth hijacked commercial airliner in rural Pennsylvania. Everyone of a certain age can remember where they were that Tuesday morning, a date and event that is simply known as “9/11.” You say it, and everyone knows what you mean.

I remember that morning like it was yesterday. We were at the lake in Maine for much of August 2001, returning home to our suburban home on the edge of Washington, DC just three weeks before that portentous date. I was still gradually settling back into my routines at home and work, hoping to hold on to the lake’s serenity as long as possible.

That morning I arose from bed around 6am hoping to get a little writing done before it was time to shower and dress and begin making my way to my office in downtown Washington. It was a beautiful late summer day, a gentle breeze and the sky a robin egg blue. I walked the block to the bus stop and shortly thereafter I was sitting on the Metro for the short ride into the center of the city. People were reading newspapers and magazines while others stared vacantly forward or out the window at the urban landscape before we dipped underground at Union Station. It was an ordinary morning commute in every way.

Leaving the station and taking the escalators to the street level I stopped at the local deli for a cup of coffee and within a few minutes I was at my desk and looking through what I had to do that day. I walked to the other side of our suite of offices to check my mail when I realized that I was the only one around. The usual hallway traffic was strangely absent and no one seemed to be in their office. As I passed by our conference room I was surprised to find most of my colleagues sitting around the table. We never had meetings this early in the day. Had I missed something?

I walked in and nobody seemed to notice my arrival; everyone’s eyes were focused on a CNN reporter on the television. “What is going on?” I inquired. “Apparently a plane has crashed into the World Trade Center,” came the reply. I sat down and watched as a thick column of black smoke rose from the upper stories of one of the towers. The information was sketchy at that time. Was it a plane? What kind of a plane was it? Big? Small? The newscasts on all the channels were saying pretty much the same thing. It was only speculation. In the meantime there were televised scenes of New York City’s emergency response teams - the police and fire department - arriving at the plaza at the base of the towers. As we watched we were suddenly horrified to see a large commercial jet fly directly into the mid-section of the second tower followed by a large, fiery explosion and a shower of debris onto the streets below. Suddenly the speculation came to an abrupt end. What we were watching was an intentional attack on the United States. But who was responsible? Shortly thereafter we heard a very large plane pass directly over our building and a few minutes later the television was showing smoke and fire at the Pentagon. Another plane had crashed there. Soon the cry of sirens could be heard and fleets of police cars and fire trucks began to move through the downtown streets of Washington. I walked outside and I could see the smoke from the Pentagon as it gradually dissipated into the blue, late summer sky. Fighter jets and helicopters were flying low over the city. I returned to the conference room in time to see the twin towers collapse into piles of wreckage and clouds of dust and debris over lower Manhattan. Fires raged at the Pentagon.

What followed seemed at the time like an eternity of confusion. The radio and television broadcasts were full of guessing and wild speculation. There were reports of bombs going off around Washington, that more hijacked planes were heading toward targets in the city. The Capitol . . . the White House only two three blocks from my office; I could see the flag waving from its roof. Suddenly more police cars were everywhere you looked. Soldiers in Humvees cruised up and down the streets just below my office window. What should we do? Should we stay where we were? Should we go somewhere, and if so, where? All we knew was that something very terrible was happening all around us. Finally came the word to evacuate. Get as far away from downtown as possible. I threw a few things in my bag and called home to tell Sally Ann I was safe and walking out of the city. I locked my office and joined the multitude as we flooded out of Washington on every compass heading, keeping our eyes on the sky and calling friends and family on cell phones to assure them we were safe . . . or were we? We still had no idea what was happening. I recall that there was very little talking; nobody really knew what to say each other. Once I got far enough away from downtown I called Sally Ann and she drove down to pick me up and take me the rest of the way home. Neighbors gathered to watch the television in disbelief as the details of that morning gradually came to light. And we have been living with the consequences of those heinous acts for over a decade.

This morning I am sitting in a rustic lodge at the rooftop of New Hampshire. Those events of eleven years ago seem so long ago and so far away and remote from the tranquility of this peaceful locale. But as far away as we can get from both that place and time, we shall never forget what happened on that date that will be forever seared into on our consciousness. Live for the future, but never forget the past.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

The Passing of Seasons - Dispatches from Maine

It is hard to imagine that only a few months ago Sabbathday Lake was covered in thick ice and snow, a few brightly painted bobhouses the only interruption in an otherwise broad expanse of white The lake’s evergreen perimeter shelters the quiet and dormant seasonal cottages, including this one on True’s Point. Opened shortly after ice-out in late April or earlier May, the water and electricity are once again turned on as the cottage welcomes us back for another summer at the lake.