| |

| Copyright 2003 by Gloria Mylyk. Used with permission. Do not reproduce without permission. |

I have been telling people for the past few years that one of these days I am going to write about Monhegan Island. After visiting the island three times this summer, I am finally making good on that promise. My thanks and appreciation go out to Ruth Grant Feller, Holden Nelson, Joan Rappaport, Stan and Marion Gurspan, and many others for their stories and willingness to share them with me.

__________

Every summer since 2001 my wife and I have been spending time on Monhegan Island. This year we could not have picked a more delightful time to go. After a cold and very wet spring followed by a stormy early summer with its murderous heat, the island was on the threshold of glorious weather when we arrived in early August. It was equally beautiful later in August when we made a day trip to the island with our son Ian, who had not been there in five years, and his wife Katie who had never been to Maine. Finally, our friend Becky Parsons, who was visiting from Virginia, joined us for another day trip this past week. The summer season was over and there were fewer visitors milling about. The local lobstermen were preparing their traps for the beginning of their season on October 1.

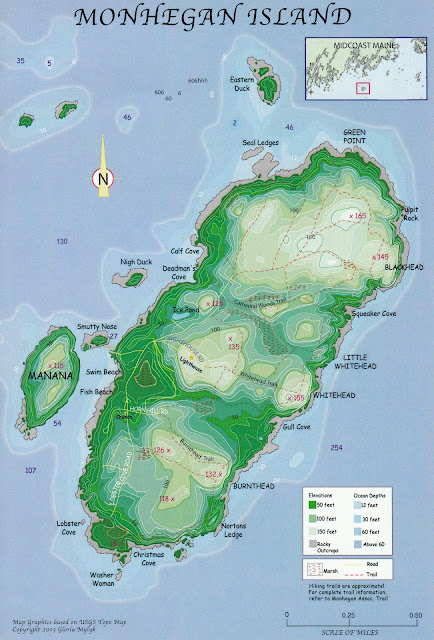

In Orhan Pamuk’s short essay “The View,” one of his frequent contributions to the Turkish political humor magazine Oküz [Ox], he describes a horse carriage ride he and his young daughter shared around Haybeliada, one of the Princess Islands in the Sea of Maramara, near his native Istanbul. Pamuk has spent many of his summers since childhood on this island and he wanted to share it with his daughter and to see it fresh through her eyes. At one point the carriage pauses at the head of a precipitous cliff where they were able to enjoy the broad panorama. “Beneath us there were the rocks, the sea, and rising out of the steam, the other islands. What a beautiful blue the sea was, with it the sun sparkling on its surface: Everything was where it should be, gleaming and immaculate. Before us was a perfectly formed world.” They admired the view in silence and wondered what made it so beautiful and appealing. “Perhaps because we could see it all. Perhaps because if we fell off the edge we would die. Perhaps because nothing looks bad from a distance. Perhaps because we’d never seen it from this height.” I have a similar feeling every summer as we anticipate our annual sojourn on Monhegan Island, a small island roughly a mile and a half long and a half-mile wide situated twelve miles off the coast of Maine, in Muscongus Bay.

Like one of this year’s visits, many of our Monhegan adventures begin with a night’s stay at the Hotel Pemaquid beautifully situated adjacent to the Pemaquid Point lighthouse which appears on the verso of the Maine state quarter. We frequently stay here the night before our departure for the island because it is just a short drive to the New Harbor wharf where we catch the morning boat out to the island. From this lighthouse on its rocky prominence we can often see Monhegan shimmering on the horizon in the early evening light as our anticipation of our visit begins to grow. From there we can also see Outer Heron Island, the White Islands, and Damariscove Island to the southwest, all of which were British fishing outposts beginning in the early 17th century, as well as many of the other 70 or so islands that populate Muscongus Bay - Western and Eastern Egg Rock, the latter being the southernmost nesting area for the Atlantic Puffin; Franklin Island with its own lighthouse. Farther to the east are the Georges Islands, among them Thompson, McGee and Burnt Island; and Benner and Allen islands, which belong to the estate of the late Andrew Wyeth who painted there each summer until his death in January 2009. And there, farther out to sea, is solitary Monhegan Island. Charles Jenney, an early chronicler of the island’s history, called it “The Fortunate Isle.” I am fortunate to visit it as often as I do (three times this summer!). I can’t think of a better way to describe it. I look out at it and I am reminded of Pamuk’s essay . . . “Everything was where it should be.”

I have previously posted brief accounts of my earlier experiences on and impressions of Monhegan Island, but there are still some interesting details I would like to share with you. On past visits to the island I have had some delightful conversations with the island’s current historian who has been coming to Monhegan since she was a toddler over 80 summers ago, and she has filled me in on the island’s history far beyond anything I already knew. Our innkeeper at the Monhegan House, where we always stay when we are on the island, has been a wonderful source of information, anecdotes, and scuttlebutt as his family has also been associated with the island since the early 1920s, and he has been coming to the island since he was a kid. I have chatted with full-time islanders and those who have been coming for summers dating back almost fifty years. Also, I have done reading and studied records in the island library to fill in some of the empty places. Monhegan Island has a very rich history, far more than I can share with you here. But here are a few salient thoughts (random and otherwise) about this most fortunate of isles.

Monhegan is one of the very few permanently inhabited offshore islands in Maine. The English explorer John Smith, who first named this region “New England,” arrived in the island’s harbor in 1614 and archeological evidence on Manana, the small treeless and whale backed island which provides protection for the anchorage, suggests that seafarers of one sort or another have been on and around the island for at least a thousand years. Although fishermen have used the island as a base of operations for centuries, permanent settlement did not commence until circa 1780 with the arrival and residency of the Trefethren, Starling and Horn families. The earliest tombstone in the island cemetery on Lighthouse Hill belongs to an infant who was born and died on the island in 1784. A few homesteads and their out buildings were constructed along with several fish houses along the harbor’s rocky edges and its two small sand beaches. Several of these fish houses are still standing and in use in some fashion today. A village of sorts was beginning to take shape on the island as members of the three families began constructing new homes and farms. It followed no plan as it developed; its austere buildings arose where they proved to be most practical for their purpose. In December 1822, the Province of Maine separated from Massachusetts and joined the Union, although Monhegan was retained by the Commonwealth. The three original families purchased all of Massachusetts’ remaining island interests for $200 in July 1823 and the island was granted to the new State of Maine. The federal government appropriated money to construct a lighthouse in 1822 and the original tower was situated 175 feet above sea level. It was razed in 1850 and replaced with the current structure. The light was automated in 1960.

The island was established as a “Plantation” - an unincorporated community in Maine - in 1839 (later within Lincoln County) and its population began to grow in the mid 19th century as new families arrived and purchased parcels of land from the original owners. New houses and barns were constructed and by 1850 there were fifteen households on the island. An island school house was constructed in 1847 and the school, segregated by sex, was established the following year. Besides its use as a classroom, the school house has long hosted other island events such as dances, shows, lectures, and various public meetings.

The federal government purchased a small tract of land on neighboring Manana island and in 1855 a fog signal keeper’s house was erected and a 2500 pound hand-wrung bell was installed (the bell is now on the top of Lighthouse Hill). A foghorn was installed in 1870,and a steam whistle in 1876 to replace the horn. A new and improved horn was installed the following year to replace the whistle. A compressed air siren was finally installed in 1912. Today the lighthouse and the fog signal (also fully automated) are known by sailors and navigators up and down the coast of Maine.

Between 1850 and the 1870s the population of Monhegan grew from 72 to 185 residents and fishing and farming remained the major means of subsistence. A non-denominational community church was constructed in 1880 and the islanders were ministered to by visiting members of the cloth during the summer months. A minister from the mainland came one weekend each month during the winter, a practice that continues to this day.

The world beyond Muscongus Bay discovered Monhegan during the last quarter of the 19th century. In 1877, Sarah and Wilson Albee purchased half interest in a house formerly owned by the Trefethren family and opened the Albee House, the first boarding establishment on the island. It eventually became the current Monhegan House, the island’s first hotel. Life on Monhegan was changing. Most of the farms and pasture land fell into disuse by the turn of the century; there was little livestock left on the island and many of the few remaining barns began to disappear. The farmland and pastures were eventually reclaimed by dark spruce woodlands. Monhegan was nothing more than a small weather-beaten fishing village.

The late 19th century also signaled the genesis of a flourishing artist community on Monhegan. By 1890, the Albee House was popular with a growing number of artists while still others were taken in by island families. The English born and Boston-based artist and photographer S.P. Rolt Triscott and his student Sears Gallagher, a promising artist in his own right, arrived on the island in 1892 and stayed at the Albee House. Triscott returned again the next year and purchased a house not far from the Albee House and began a long relationship with Monhegan that lasted until his death on the island in 1925 (he is buried in the island cemetery). George Everett, another artist, came to live year round on the island in 1896 and turned speculator, purchasing island real estate from the locals and platting building lots on Horn’s Hill, on the village’s southern reach. Gallagher continued to summer on the island for the next six decades as more Boston artists followed in Triscott’s footsteps. Eric Hudson first noticed the island in 1897 while sailing up the Maine coast from Boston to Mount Desert Island farther Down East. He returned the following summer and built a cottage and continued to paint on the island. Soon artists from as far away as Philadelphia, New York and Boston were traveling by train to Maine and then catching a coastal steamer destined for Monhegan.

Robert Henri and members of the Ashcan School in New York City, known primarily for its urban realism, first came to the island in 1902 and they continued to make annual visits during the summer months. “It is a wonderful place to paint,” Henri writes. “So much in so small a place one could hardly believe it.” Now the artists focused their talents on Monhegan’s varied landscapes and the powerful seascapes that surrounded the island. The Old Lyme Colony painters from Connecticut arrived in 1908, staying at The Influence, one of the oldest surviving buildings on the island (circa 1820s). Soon other noted artists were associated with the island.

The artist Rockwell Kent first came to the island with Robert Henri. Finding Monhegan to be the “land of promise,” he subsequently purchased a piece of land platted by Everett and built a small cottage where he wintered on the island in 1906-1907. He built another cottage for his mother at Lobster Cove, on the southern end of the island, in 1908. Since April 1968 it has belonged to Jamie Wyeth who still comes to the island frequently to paint. (The Farnsworth Art Museum, in nearby Rockland, Maine, is featuring an exhibit this year focusing on Kent’s and Wyeth’s long association with Monhegan.) Kent, who continued to do manual labor and work on construction projects on the island, also built another small studio in the village in 1910 and operated a small art school there for a time. “Truly I loved that little world, Monhegan, “Kent wrote. “Small, sea-girt island that is was, a seeming floating speck in the infinitude of sea and sky . . . .” He also admired the islanders. “I envied them their strength, their knowledge of boats and their familiarity with that awesome portion of the infinite sea. I envied them their worker’s human dignity . . . .” The locals went about their work and left the artists and other visitors to tend to their own. Kent finally left Monhegan in 1953 and James Fitzgerald, an artist long connected with the area around Monterey, California, later used Kent’s cottage and studio into the early 1970s and painted some of his most interesting work there. One cannot think of Monhegan without conjuring up the works of Kent, Triscott, Gallagher, Henri, Fitzgerald, George Bellows, Edward Hopper, Reuben Tam, Andrew Winter and a host of other artists. Three generations of Wyeths have also painted on Monhegan.

By 1910 new summer cottages had been built by artists and others as the land of the original three families was being “gobbled up” by newcomers. By this time a second island hotel, the Island Inn, was established on a hillside facing the harbor and the wharf which still serves the island today. Kent described the two hotels as “big barn-like things, exteriorly as uninviting as their tasteless insides warranted. But what are we to expect, we touring picture painters and summer tourists and visitors - ‘rusticators’ - they call us. Don’t we invite just such monstrosities for our convenience? Don’t they, perhaps, match us?” Soon the summer community began to outnumber the permanent island inhabitants. The village was developing with the expansion of the unimproved roads (glorified paths actually), the establishment of a post office and regular mail service by boat from Port Clyde (originally known as Herring Gut), and the opening of various shops catering to the growing island population. Ice required for refrigeration of food was cut from a small island pond during the winter and stored in an adjacent ice house. The cutting and storage of ice continued until the early 1970s when electricity came to the island replacing gas and kerosene.

Many of the island residents, both permanent and summer rusticators, joined the visiting artists in celebrating the tercentenary of John Smith’s landing on the island, in 1914. This was the first golden era of life on Monhegan. Unfortunately, the advent of World War I that year brought this era to a quick end as life on the island returned to that of a relatively quiet and secluded fishing village throughout the war years. It did not remain so for long, however, and several new houses and cottages were constructed in the early 1920s. With a further increase of the postwar summer population came more work for the year round population of approximately 140 who kept themselves busy laying in more food and supplies and opening up and taking care of the summer cottages. More artists, such as Abraham Bogdanov and Mary Townsend Mason, frequented the island. A small village library was constructed and opened in 1930 and is still operated by a Library Association. Next to the village post office was “the Spa, a small soda fountain with a bingo parlor and recreation hall upstairs. Despite this new lease on life, new construction on the island slowed during the 1930s due to the long-term effects of the Great Depression.

The year-round population in 1940 had fallen to around 70, and this number dropped even lower during World War II when several eligible island men went into the military. Luckily all returned home safely although two were prisoners of war for a time. The island was on a war footing as the entire island was blacked out throughout the war and the Coast Guard patrolled the waters around the island and posted a sentry on the headlands on the eastern side of the island (the highest cliffs on the coast of Maine where I frequently go to “look toward Portugal”). Very little land was purchased during the war and there was almost no new construction of summer cottages.

Some new construction occurred on the island beginning in 1947 and life was returning to normal by 1950. Summer visitors were returning in increasing numbers and several artists began looking for or constructing cottages and studios. Monhegan also underwent an artists renaissance after the war. Andrew Winter, a native of Estonia who first came to Monhegan with Jay Connaway in the 1920s, returned to the island with his artist wife Mary, in 1940. Both lived and painted year round in a house near the island wharf until Andrew died in 1959 (his widow sold it in 1963). Like Rockwell Kent before him, Winter did odd jobs around the island and lobstered from his dory. It was also after the war that the new Monhegan House developed a close association with the Ashcan School in New York and hosted a number of artists visiting the island during the summer.

The years of postwar prosperity brought with them the possibility that the island might become the target of uncontrolled development and quickly outgrow its ability to sustain a way of life so many - the island’s permanent residents and summer visitors alike - had come to appreciate. To preserve the island’s unique character, Ted Edison, the son of Thomas Edison and a regular summer resident who is also buried on Lighthouse Hill, and a number of like-minded individuals established the Monhegan Associates, Inc., in 1954, to protect the island from over-development. It eventually purchased almost 500 acres of undeveloped land outside the village with the intention of maintaining its almost pristine natural state in perpetuity.

Today Monhegan Island remains much as it has been for many years. Once the summer residents and visitors leave in late September, the island is again a quiet fishing community. Unlike other lobstering operations along the coast of Maine, Monhegan’s lobstermen have chosen to fish only during the late fall and winter months, setting their traps with a great deal of ceremony on October 1 (until recently they waited until December 1), and finally pulling them for the season, typically at the end of June. While buyers do come to the island from time to time, there are no facilities for processing or marketing the catch on island and so it is transported to Port Clyde and Rockland, on the mainland. The rest of the year lobstermen find other pursuits to keep them busy. Island life in these northern climes always requires constant care and maintenance of the village buildings.

Come June the artists and summer people begin to return to the island to open their cottages and studios after a long winter off-island. Soon daily boats operating out of Port Clyde, New Harbor and Boothbay Harbor are docking at the wharf and disgorging flocks of daytrippers and others who have come to hike the island’s miles of nature paths, to paint and take photographs, or otherwise enjoy the peace and quiet of this secluded and most fortunate isle.

So, when I stand on the mainland and stare out at Monhegan Island, whether I plan to head out there the next day or not, I understand Pamuk when he describes the view from the rocky headland of Turkey’s Haybiliada Island. Everything does seem to be where it is supposed to be.

No comments:

Post a Comment