In my last posting on April 8, I mentioned a few of my close encounters with major thunderstorms and tornados. This came about after watching videos about tornados and the exploits of storm chasers in “Tornado Alley” of the Great Plains. These storms are created when dry cold air moving south from Canada meets warm moist air traveling north from the Gulf of Mexico.

During the spring and early summer storm chasers set out in search of “towers,” the looming cumulus clouds that can be the first stage in the formation of a supercell storm. Storm chasing often involves driving hundreds of miles in search of active severe thunderstorms. Many chasers spend a significant amount of time forecasting, both before going on the road as well as during the chase, utilizing various sources for weather data. Once located the serious chasers employ Doppler radar to spot rotation that spells the potential birth of a tornado. The idea is to get as close to the storm – even in its direct path – as safety will allow in order to take photographs, make videos, and record data. Many storm chasers are trained meteorologists seeking to learn more about how these storms work. Others are simply in it for the chase and bragging rights, and perhaps earning a modest salary selling data, video, and photography they collect.

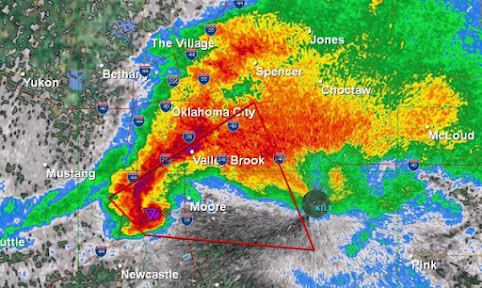

Storm chaser, or spotters, are necessary as Doppler radar, which was first introduced in the 1970s, illuminates elements of these developing storms yet it can only detect storm signatures. It does not show where a tornado has actually formed or what it looks like on the ground. In the mid-1970s, the National Weather Service (NWS) increased its efforts to train storm spotters so they could identify key storm features such as severe hail, damaging winds, and tornadoes, as well as storm damage and flash flooding. According to recent statistics, there are more than 200,000 trained spotters in the United States.

Storm chasing became more popular after the 1996 release of the film Twister starring the late Bill Paxton and the late Philip Seymour Hoffman in one of his earlier film roles. It provided an action-packed yet fictionalized glimpse into the community of professional spotters hoping to put an instrument package – called “Dorothy” after the character in The Wizard of Oz who was suck up by a Kansas tornado – directly into the damage path of an EF5 tornado in order to gather data from the storm’s interior . . . what Hoffman refers to as the “suck zone.” But storm chasing is more than walking outside, or getting in your car, to look at the sky.

One has to know what one is looking for and what to do when a tornado is spotted. Working on the ground, however, these spotters can provide definitive information whether a storm seen from a distance is a supercell and provide visual information on the storm's shape and structure, including updraft towers, rotation in the wall cloud, striations, strength of inflow, and position of the precipitation core in relation to the wall cloud. A vast majority of tornadoes occur with a wall cloud on the backside of a supercell. Most of these signs – temperature, humidity or pressure inside a tornado – will not show up on Doppler radar. Spotters also look for ground disturbances beneath the wall cloud as a tornado forms not from the clouds down, but from the ground up; it might already be on the ground before the funnel becomes visible.

Spotters must also be familiar with the different shapes a tornado might take. The most common form is the relatively narrow vortex, or rope, tornado. Most tornadoes begin and end their life cycle as a rope tornado before growing larger or dissipating. Once on the ground a tornado will generally evolve into a cone shape which is more dangerous than rope tornadoes as their tracks leave a wider damage path. A wedge tornado has the appearance of an upside-down triangle and wider than it is tall. Its damage path is also broader than a rope or cone tornado. Perhaps one of the most fascinating storms to observe is the multi-vortex tornado when two or more funnels clouds occur simultaneously from the same wall cloud. Smaller “sub-vortices” will rotate around a larger primary vortex and often they will commingle into a damaging wedge tornado. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wp8E_GANqgk

There are six categories of tornado – EF0-EF5 – on the Enhanced Fugita Scale established in 2007 and based on estimated wind speeds and relative damage. The previous Fugita Scale established in 1971 was based solely on the amount of damage. The NWS is the only federal agency with authority to provide official tornado EF Scale ratings based on the highest wind speed occurring within the damage path. Once again the NWS relies on ground spotters to ascertain this information. An EF0 tornado has winds estimated at 65-85 mph creating general light damage. An EF5 – the so-called “finger of God” – has wind speeds of over 200 mph causing devastating damage. The largest and strongest tornado on record was the EF5 El Reno wedge tornado occurring in Oklahoma on May 31, 2013. According to reports, it grew to a width of over 2.5 miles with a wind speed reaching 302 mph. Fortunately the storm occurred mostly in open country and so damage and lost of life was relatively low for such an intense storm. Nevertheless, 20 people lost their lives and over 100 others were injured during its 40-minute rampage. There was another EF5 tornado in and around Oklahoma City eleven day earlier with 215 mph wind killing 24 people and causing extensive and widespread damage.

Watching videos of storm chasers in action it is not difficult to differentiate the professionals from the hobbyists. Those in the know describe what they are doing and seeing and we can hear then making their detailed reports to the NWS and local radio stations to warn of tornados on the ground. The hobbyist narrative seems to be a repetitious litany of “oh my god,” “don’t get too close,” stop here,” and my favorite “is that a tornado?” Very often these catechumen are thrown off by so-called scud clouds which are nothing more than cloud fragments hanging lower than the rest of the clouds. Some may even appear to be have small funnels at their base. These are not tornados, but rather condensation suspended from the main layers of thick cumulonimbus storm clouds. Rotation is the key for the formation of a tornado and this is why it is important to have trained professional on the job. They know what they are doing, what they are looking for, and how to respond to changing conditions. Yet sometimes even this is not enough.

There are many inherent dangers involved in storm chasing ranging from the tornado itself, as well as from lightning, large and damaging hail, hazardous road conditions, downed power lines, and storm debris. There can be reduced visibility from heavy rain, and in some situations severe downburst winds may push automobiles around. Most weather-related hazards can be minimized if the storm chaser is knowledgeable and cautious while maintaining a safe distance and having an escape route should the storm suddenly change direction. Adding to these weather-related hazards are distractions to the chaser’s attention while driving – watching the sky, navigating, communicating, checking instruments, or taking photographs and videos. Most professional chasers work in teams to avoid dangerous multi-tasking.

Three of the El Reno fatalities were experienced professional storm chasers, the first known chaser deaths inflicted directly by weather. Several other chasers were also struck and some injured by this tornado and its parent supercell's rear flank downdraft. The three died when the storm suddenly changed direction and their vehicle was destroyed while attempting to place a TOtable Tornado Observatory (TOTO), on which the Dorothy packet in the Twister film was based, in the damage path of that historic tornado. This tragedy may have been prevented had they been equipped with mobile Doppler radar which has now become proforma in serious storm chasing circles as it provides near real-time updates on intensity and movement of the developing storm.

As exciting as the chase might seem, it is not something for the fainted hearted. Another good reason for leaving storm chasing to the professionals who know what they are doing.

No comments:

Post a Comment